La intrusa

Saturday, April 14, 2012 at 17:46

Saturday, April 14, 2012 at 17:46 A short story ("The intruder") by this Argentine. You can read the original here.

2 Kings, I, 26.

They say (which is improbable) that the story was told by Eduardo, the younger of the Nelsons, at the wake of Cristian, the elder, who died a natural death in the 1890s in the administrative area of Morón. What we can say for certain is that someone heard it from someone else during that long, lost night between matés, and repeated it to Santiago Dabove, from whom I heard it. Years later I was told the story again in Turdera, where it had taken place. In short, this second, somewhat tidier version, confirmed Santiago's account – albeit with some small variations and divergences, which is to be expected. I am writing it now because, if I am not mistaken, it contains the brief and tragic essence of these remote bordermen of yore. Although I shall write with integrity, I foresee succumbing to the literary temptation of accentuating or adding a detail here and there.

They say (which is improbable) that the story was told by Eduardo, the younger of the Nelsons, at the wake of Cristian, the elder, who died a natural death in the 1890s in the administrative area of Morón. What we can say for certain is that someone heard it from someone else during that long, lost night between matés, and repeated it to Santiago Dabove, from whom I heard it. Years later I was told the story again in Turdera, where it had taken place. In short, this second, somewhat tidier version, confirmed Santiago's account – albeit with some small variations and divergences, which is to be expected. I am writing it now because, if I am not mistaken, it contains the brief and tragic essence of these remote bordermen of yore. Although I shall write with integrity, I foresee succumbing to the literary temptation of accentuating or adding a detail here and there.

In Turdera they were called the Nilsens. The parish priest told me that his predecessor remembered, not without some surprise, having espied in their family home a well-worn Bible bound in black with Gothic lettering; handwritten numbers and dates peppered the last pages. It was the only book in the house – the hazard-ridden saga of the Nilsens, lost as everything would eventually be lost. The sprawling house, which no longer exists, was of unfinished brick; from the hallway two patios split off, one in red tiles, the other of dirt. Few, as it were, would enter there; the Nilsens closely guarded their solitude. In the dismantled rooms they slept on cots. Their luxuries were their horses, their harnesses, their short-bladed daggers, their lavish Saturday attire, and their trouble-making alcohol. I know that they were tall with long, reddish hair. Denmark or Ireland, of which they had never heard, coursed through the veins of these creoles. The neighborhood feared The Redheads; it was not impossible that they might have had someone's death on their conscience. One time, standing back to back, they brawled with the police. It is said that the younger Nilson had an altercation with Juan Iberra and in the end was not the worse off of the two, which, in our understanding, is rather impressive. They were herders, towers, rustlers, and sometimes cardsharps. They were renowned as misers; only with drink and gambling did they become generous. No one knew anything of their relatives or even where they came from. They were the owners of a cart and a team of oxen.

Physically they differed from the usual breed that had lent its outlaw nickname to the Costa Brava. This fact and what we don't know can help us understand how united they were. To get along poorly with one of them was to anticipate having two enemies.

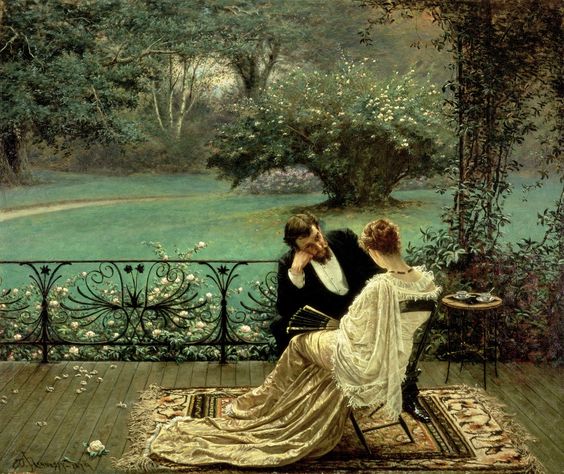

The Nilsens were rakes, but their amorous episodes had hitherto involved the hallway or their baleful house. There was no lack of commentary, however, when Cristian went to live with Juliana Burgos. It was true that in this way he was gaining a servant. But it was no less certain that he plied her with awful knickknacks and showed her off on holidays, on those poor holidays in the slums where both the broken and the regal were banned and where, nevertheless, there was dancing and a lot of light. Juliana had a dark complexion and almond-shaped eyes; someone only had to glance at her and she would smile. She was not bad-looking amidst a modest neighborhood in which work and negligence conspired to wear women out.

At the beginning Eduardo accompanied them. Then he took a trip to Arrecifes for who knows what type of business; upon his return he brought home a girl he had picked up on the way back, and a few days later threw her out. He became more surly; he got drunk only at the grocery store and didn't socialize with anyone. He was in love with Cristian's woman. The neighborhood, who perhaps knew this before he did, foresaw with treacherous happiness the latent rivalry of the brothers.

One night, coming back late from the corner, Eduardo espied Cristian's dark horse tethered to the fence. His older brother was waiting for him on the patio in his best clothes; the woman was coming and going with maté in her hand. Cristian said to Eduardo:

"I'm going out partying at the Farías' place. Here you have Juliana; if you wish, make use of her."

His tone wavered somewhere between commanding and cordial. Eduardo remained looking at him for a while; not knowing what to do, Cristian got up, bid farewell to Eduardo but not to Juliana, which was something, mounted the horse and, without rushing, set off on a trot.

From that night on they shared her. It is possible that no one knew the details of this sordid union, which exceeded the decencies of the slums.

The arrangement went well for a few weeks, but it could not endure. The brothers did not mention Juliana's name to one another, not even to call her, but instead looked for, and found, reasons so as to disagree. They argued over the sale of some hides, but what they argued over was another matter. Cristian tended to raise his voice as Eduardo remained silent. Without knowing it, they were jealous of one another. In a harsh suburb a man did not say – not even to himself – that a woman could matter to him beyond desire and possession, but both of them were in love. For them, in a way, this was humiliating.

One evening, on Lomas square, Eduardo crossed paths with Juan Iberra, who congratulated him for having scored himself such an exquisite female. It was then, I believe, that Eduardo laid into him. No one could make fun of Cristian in front of his brother.

The woman would wait for both of them with animal-like submissiveness; but she could not hide her preference for the younger brother, who had not refused to participate yet had also not made her available.

One day they ordered Juliana to bring two chairs to the first patio and not linger there because they had to talk. She anticipated a long conversation and went to take a siesta, but soon thereafter they remembered her. They made her pack a bag with everything she had, not forgetting the glass rosary and the crucifix that her mother had left her. Without explaining a thing to her, they placed her in the coach and undertook a silent and tedious journey. It had rained; the roads were very oppressive and it may have been around five in the morning when they reached Morón. Here they sold her to the madam of a brothel. The deal was already done; Cristian collected the amount and later divided it with his brother.

In Turdera, the Nilsens, hitherto lost in the tangle (which was also a routine) of this monstrous love, wished to renew their old life of men among men. They returned to their riggings, to their cockpit, to their casual binges. Perhaps at some point they believed themselves saved; but they would incur, each for his own part, unjustified or extremely justified absences. Just before the end of the year, the younger brother said that he had to go to the capital. Cristian went to Morón; on the fence of the house we all know he found Eduardo's peach-colored horse. He entered; inside the other brother was waiting his turn. I believe Cristian said to him:

"If we keep this up, we are going to tire out the horses. Better that we keep her with us."

He spoke with the madam, produced some coins from his belt, and they took her away. Juliana went with Cristian; Eduardo spurred on his peach-colored horse so as not to have to look at them.

They returned to what has already been mentioned. The infamous solution had failed; both of them had given in to the temptation of cheating. Cain certainly wandered through these parts, but the affection between the Nilsens was very strong – who knew what rigors and perils they had shared! – and they preferred to vent their exasperation on outsiders. On a stranger, on the dogs, on Juliana, who had brought them discord.

The month of March was about to end and the heat was not letting up. One Sunday (on Sundays people are supposed to come home early) Eduardo, returning from the grocery store, saw that Cristian was yoking the oxen. Cristian said to him:

"Come, we have to leave a few hides at the Pardo's place. I've already loaded them; let's take advantage of the fresh air."

The Pardo's business was, I believe, more to the south; they took the Camino de las tropas, the cattle route, then a detour. The field was growing bigger with the night.

They came upon a scrub-land; Cristian took out the cigarette he had lit and said, without the slightest haste:

"To work, brother. The caracaras will help us afterwards. Today I killed her. May she remain here with her clothes and do no more damage."

They embraced, almost crying. Now yet another shackle bound them together: the sad sacrifice of the woman and the obligation to forget her.