Pasternak, "Heinrich von Kleist" (part 2)

Monday, July 23, 2012 at 06:35

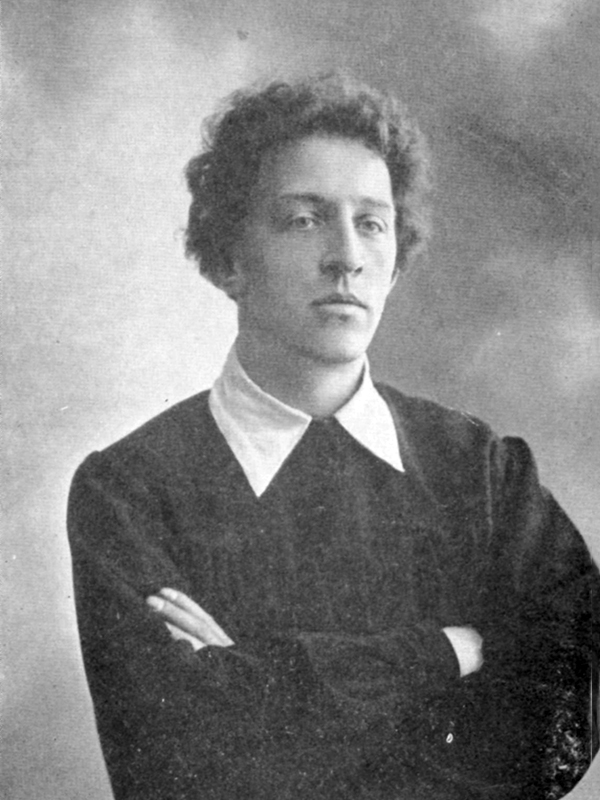

Monday, July 23, 2012 at 06:35 The conclusion to an essay by this Russian poet on this German man of letters. You can read the original in this omnibus.

The consequences of Goethe's mysterious and secret dislike for Kleist extended throughout the latter's life. Attempts to clarify the matter only exacerbated the enmity. Kleist did not know that it was to the tactlessness of intriguers that he owed his notoriety to Goethe, who was like a sacred object to him, who could have brought him happiness, and to whom he must have seemed like a foolish copy of Werther. In 1809 Goethe wrote a man of letters the following about Kleist: "I am right to reproach Kleist because I loved and ennobled him. But either his development has been delayed by time, as one may notice in many nowadays, or for some other reason he has not justified his potential. Hypochondria is killing him as both a person and a poet. You know full well how much effort I exerted so that his Broken Jug would be performed in our theaters. And if nevertheless he did not succeed, we may attribute this to the fact that a talented and witty scheme may be lacking in naturally developing action. But to impute his failure to me and even, as has been proposed, to consider issuing me a challenge – this is, as Schiller says, evidence of the severe distortion of nature, excusable only by an extreme irritability of the nerves or by an illness."

Kleist's life assumed a certain quality during the time of his return from Switzerland: he was recognized and acknowledged. Beside his innate timidity, his proud and secretive nature, arose the lack of freedom of a person noticed by his century. This gave his unhappiness legitimacy.

He tried to establish himself somewhere, first in Königsberg then later in Dresden. Constantly distinguishing himself in his methods, he wrote some remarkable and striking works, like his brilliant stories, The Earthquake in Chile, The Marquise of O., the aforementioned Michael Kohlhaas, and others. As if possessed by some kind of demon he fled from the favors of any fate, woman, work, or safe haven, and the wartime chaos aided him in his mobility. These aimless meanderings were sometimes complicated by the interference of the police.

Such was the case, for example, during his second trip to Paris when, in a frenzy, he burned his Guiscard and quarreled violently with von Phull, the future general and his friend, whom he obliged to race among the morgues of Paris the whole next day in search of his body. Such was the case on the French coast as the army was preparing itself for disembarkation to England. Kleist believed that it was the fate of the troops to be buried at the bottom of the ocean. They found Kleist in Saint-Omer where he had gone to enlist as a volunteer. Here he was arrested on suspicions of espionage; only thanks to the efforts of the Prussian emissary Lucchesini did he avoid getting shot. Instead, he was sent back to his homeland. In 1807, on exactly the same suspicions, he was deported from French-occupied Berlin to the French Fort de Joux, the place of the recent captivity and death of the black consul Toussaint Louverture. This circumstance informed Kleist's fearful tale, The Engagement in Santo Domingo.

The years which we have covered in this brief overview were a turning point for Kleist's moral structure. He had once been ruled by fibs and fictions; his delusions had triumphed over facts. But now this would all change. In 1806 Prussia lost the battle of Jena-Auerstedt. Every facet of life fell into disarray; devastation set in. Kleist stopped receiving the financial support earmarked for him by Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. Before him hovered the spectre of indigence.

The assumption that politics would always trump life seemed merely like the unspoken exaggeration of publicists; yet in the years of a century's upheavals it is true. When, in 1808, Spain rose up against the French dominion, this affected countless other corners of the world.

Kleist was then in Dresden. He nurtured personal enmity towards Napoleon of the kind he had only experienced towards Goethe. The events in Spain animated and inspired him. With his usual prolificness Kleist wrote, in a little more than a year, three five-act dramas: Penthesilea, based on themes from Greek mythology; The Trial by Fire, a dramatic fairy tale about German knights in the Middle Ages; and The Battle of Teutoburg Forest, a patriotic drama glorifying medieval German warfare. But what was Kleist supposed to feel when in the spring of 1809 one of the German states, Austria, following Spain's example, emerged from its thrall to its conqueror? Kleist rejoiced and, abandoning his affairs and job, sought to enlist in active duty in the Austrian army. In a camp near Aspern some acquaintances of his, as well as unpleasantries experienced twice before, awaited him. He seemed suspicious. With some difficulty he wriggled his way out of this confrontation and left to Prague. It was here that he learned of the catastrophe at the Battle of Wagram – a blow from which he would never recover.

In order for the last chapter of his life to stand out more prominently, no further information on Kleist will be provided at this time. Some are convinced that during these months he was preparing an assassination attempt on Napoleon; rumors spread about his demise; and this is precisely when he arrived in Berlin.

He came in coldest winter. He was no longer the odd crank of before, who even in good times saw everything in the blackest of hues, but a level-headed warrior against the true iniquities of fate. In cold and desolation, regardless of what means it required, he would develop a reality that now seems incredible. He wrote The Prince of Homburg, his very best work, an historical drama realistic in its performance, concise, witty, flowing and well-paced, a mix of the fire of lyric poetry and a clear sequence of events. He took the reins of an evening paper for which he would compose an endless amount of small articles and stories over a period of several months. Only a negligible part of these writings has been identified amidst the pile of anonymous material in which it appeared. He finished a novel in two books that vanished without a trace in a Berlin print shop, and prepared for publication the second volume of his peerless stories.

All this time his destiny did not abate. Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, his protectoress, died. The ministry that had been so lenient to him and his newspaper was replaced. The new cabinet began imposing limitations on the paper, devaluing the business enterprise itself, which finally collapsed. Kleist ended up in debt. The Prince of Homburg did not get published. The stories already in print no longer interested anyone. Then in February of that terrible winter of 1811 for which no end seemed in sight, Kleist remembered his first distraction, his first conscious steps towards a calling, his childish game of playing soldier, penned a farewell to his illustrious name, and reenlisted in the army. His request would soon be met, but it proved impossible to get him into uniform. He beseeched the king anew to loan him money for equipment and awaited a reply. Summer passed by and no answer had been received. Autumn came with strong evidence of the return of that winter without end.

Kleist had a female acquaintance, the terminally ill musician Henriette Vogel. One time when they were playing together as lovers might, she said that if she could find a partner she would like to part with this life. "Why then did we even start all this?" said Kleist, and offered himself up as a companion on this treacherous road.

On November 20, 1811 they went out to the Wannsee near Berlin, a site for long strolls outside the city. They took two hotel rooms by the lake and spent the evening and a part of the next day there. All the morning through they strolled; after lunch they asked that a table be taken out to the dam on the same side of the creek. From there two shots were heard at dusk. One Kleist discharged into his girlfriend, the other he used to end his own life.

Had our interest in Kleist arisen recently it would have been an inexplicable anachronism. Kleist began to be studied before the war. In 1914 together with Sologub and Wolkenstein, I translated The Broken Jug. The remaining translations of The Prince of Homburg, The Family Schroffenstein, and Robert Guiscard were completed between 1918 and 1919.

Getting to know Kleist's work was abetted by the publications in Vsemirnaya Literatura and Academia. The first is prefaced by a marvelous article by Sorgenfrei; the second supplemented by interesting commentary by Berkovsky. The translations of Kleist's stories by Rachinsky and Petnikov remain above any possible praise.