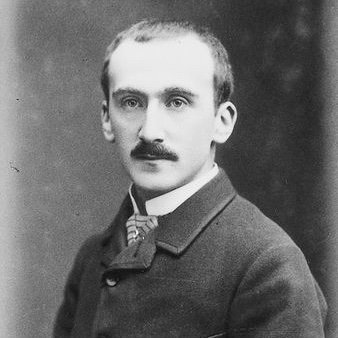

Bergson, "The possible and the real" (part 3)

Tuesday, July 19, 2011 at 16:19

Tuesday, July 19, 2011 at 16:19 The conclusion to an essay by this philosopher and man of letters. You can read the original as part of this collection.

In the course of the Great War, newspapers and magazines sometimes turned away from the terrible worries of the present to consider what would happen later on, once peace had been regained. The future of literature in particular preoccupied them. One day I was approached and asked how I saw the future. Somewhat confused, I declared that I did not see it at all. "Don't you see at least," was the reply, "a few possible directions? We admit that we cannot foresee the details; but you at least, you the philosopher, have an idea of the set of possibilities. How do you imagine, for example, the great dramatic work of tomorrow?" I will always recall my interviewer's surprise when I answered him: "If I knew what the great dramatic work of tomorrow would be, I would create it myself." I saw clearly enough that he thought the future work locked away, since then, in who-knows-what cupboard of possible works; in consideration of my age-old relationship with philosophy, I was supposed to have obtained the key to that cupboard.

In the course of the Great War, newspapers and magazines sometimes turned away from the terrible worries of the present to consider what would happen later on, once peace had been regained. The future of literature in particular preoccupied them. One day I was approached and asked how I saw the future. Somewhat confused, I declared that I did not see it at all. "Don't you see at least," was the reply, "a few possible directions? We admit that we cannot foresee the details; but you at least, you the philosopher, have an idea of the set of possibilities. How do you imagine, for example, the great dramatic work of tomorrow?" I will always recall my interviewer's surprise when I answered him: "If I knew what the great dramatic work of tomorrow would be, I would create it myself." I saw clearly enough that he thought the future work locked away, since then, in who-knows-what cupboard of possible works; in consideration of my age-old relationship with philosophy, I was supposed to have obtained the key to that cupboard.

"But," I say to him, "the work of which you speak is not yet possible."

"But it simply has to be possible, so that it will come to pass."

"No, it is not. That said, I will grant you that it will have been."

"What do you mean by that?"

"It's very simple. I mean that a man of talent or of genius will emerge and create a work: and then it will become real and even, by the same means, retrospectively or retroactively possible. It would not be, it could not have been, if this man had not emerged."

"That's a bit much! You surely would not allege that the future influences the present, that the present introduces something into the past, that action goes back through the course of time and leaves its mark behind!"

"That depends. I have never claimed that one might insert some of the real into the past and thus work backwards through time. But that one might lodge there some of the possible, or, rather, that the possible might lodge itself there at any time, this is not doubtful. As reality gradually creates itself, unpredictable and new, its image is reflected behind it in the indefinite past; thus it finds it has been, at all times, possible; but just at the very moment where it begins to have always been, and that is why I was saying that its possibility, which does not precede its reality, will have preceded it once its reality has appeared. The possible is thus the mirage of the present in the past. And as we know that the future will end up becoming the present, as the effect of the mirage continues unabatedly to produce itself, we tell ourselves that in our current present, which will be the past of tomorrow, the image of tomorrow is already contained although we haven't come to grasp it. And precisely there lies the illusion. It is as if one thought that, having espied one's image in the mirror before which one has just situated oneself, one could have touched the image if one had remained behind. Moreover, in judging in this way that the possible does not presuppose the real, one admits that the realization adds something to the mere possibility: the possibility would have been there the entire time, a ghost awaiting its hour; thus it would have become reality by the addition of something, by who-knows-what transfusion of blood or life.

"One does not see that it is exactly the opposite. That, what is more, the possible implies the reality corresponding to something linked to it, because the possible is the combined effect of reality having appeared and of a device that sends it backwards. The idea, immanent to most philosophies and natural to the human mind, of possibles which would be realized by an acquisition of existence, is thus pure illusion. One might as well claim that the man of flesh and bone stems from the materialization of his image as it appeared in a mirror, under the pretext that in this real man there is everything which one finds in this virtual image with, in addition, the solidity needed so that one can touch that image. But the truth is that here one needs more to obtain the virtual than to obtain the real, more for the image of man than for man himself, because the image of man will not be drawn if one does not begin with man, and one would need more than a mirror."

This is what my interviewer forgot when he asked me about the theater of tomorrow. Maybe he was also unconsciously playing on the sense of the word, "possible." Hamlet was doubtless possible before having been realized, if one means that there was no insurmountable obstacle to its realization. In this particular sense, we call possible that which is not impossible; and it goes without saying that this non-impossibility of a thing is the condition of its realization. But the possible understood in this way is not virtual or ideally preexisting to any degree. Close the barrier and you know that no one will cross the road; from there it does not follow that you would be able to predict who will cross that road if you open the barrier. Nevertheless, you pass surreptitiously, unconsciously from the completely negative sense of the term "possible" to the positive sense. Here possibility just meant "absence of impediment"; from this you now forge a "pre-existence in the form of an idea," which is something completely different. In the first sense of the word, it is a truism to say that the possibility of a thing precedes its reality: by that you understand simply that such obstacles, once surmounted, were surmountable.***

But, in the second sense, this is an absurdity, because it is clear that the mind in which Shakespeare's Hamlet was drawn in the form of the possible would thereby have created the reality. Thus it would have been, by definition, Shakespeare himself. In vain you may imagine initially that this mind could have emerged before Shakespeare, and here is where you are not thinking about all the details of the drama. As you gradually complete these details, Shakespeare's predecessor will find himself thinking everything that Shakespeare will think, feeling everything that Shakespeare will feel, knowing everything that Shakespeare will know, perceiving therefore everything that Shakespeare will perceive, occupying consequently the same point in space and time, having the same body and the same soul; being Shakespeare himself.

Yet I insist too much upon that which goes without saying. All these considerations impose themselves when one is dealing with a work of art. We will not, I believe, end up finding it evident that the artist creates the possible at the same time as he creates the real when he is carrying out his work. From where then would we likely hesitate to say just as much about nature? Isn't the world a work of art, incomparably richer than that of the greatest artist? And isn't there just as much absurdity, if not more, in supposing here that the future is drawn in advance, that possibility pre-exists reality? Once again, I would like the future states of a closed system of material points to be calculable and, consequently, visible in their present state. But, I repeat, this system is extracted or abstracted from a whole which comprises, apart from inert and unorganized matter, organization. Take the concrete and complete world with the life and consciousness it contains; consider nature as a whole, generator of new species in forms as original and new as the drawing of any artist; follow, within these species, individuals, plants or animals, each of whom has its own character – I was about to say personality (because one blade of grass does not resemble another blade of grass any more than Raphael resembles Rembrandt); rise above individual man to the societies which unfurl actions and situations comparable to those of any drama: how can one still speak of possibles which would precede their own realization? How does one not see that if the event is always explained after the fact by such and such preceding events, a completely different event would also be explained well, in the same circumstances, by antecedents chosen differently – what am I saying? Ultimately by the same antecedents cut differently, distributed differently, perceived differently in retrospect? From the front backwards a constant remodeling of the past by the present, of the cause by the effect.

We do not see it always for the same reason, always in thrall of the same illusion, always because we treat as greater that which is less, and what is less as that which is greater. Let us put the possible in its place: evolution is something very different from the realization of a program; the doors of the future open very wide; a limitless field is liberated and released. The wrongness of doctrines – quite rare in the history of philosophy – that knew to grant a place to indetermination and liberty in this world, is not to have seen what their affirmation implied. When these doctrines spoke of indetermination and of liberty, they had in mind with indetermination a competition among possibles, and by liberty a choice between possibles – as if the possibility were not created by liberty itself! As if an entirely different hypothesis, in placing an ideal pre-existence from the possible to the real, did not reduce the new into nothing more than a rearrangement of old elements! As if it could not be taken in this way sooner or later as being calculable or predictable. In accepting the postulate of the adverse theory, we would introduce the enemy in its place. One has to make a choice of the two: it is the real which becomes possible, and not the possible which becomes real.

But the truth is that philosophy has never frankly admitted this continual creation of unpredictable novelty. Ancient thinkers were already repelled by such a notion since, being more or less Platonic in their approach, they concluded that Being, complete and perfect, was given once for all things, in the immutable system of ideas. There was nothing that could be added to the world unravelling before our eyes; on the contrary, it was nothing more than a diminution or degradation, its successive states measuring either the increasing or decreasing distance between what is, a shadow projected in time, and what ought to be, the Idea seated within eternity, and sketching out the variations of a deficit, the changing form of a void. It was Time that would spoil everything. Modern thinkers, true enough, are fond of a different point of view. They no longer treat Time as an intruder, a perturber of eternity; but all the same they reduce it to a mere semblance. The temporal is therefore nothing more than a confused form of the rational. What is perceived by us as a succession of states is conceived by our intelligence, once the fog has lifted, as a system of relations. The real becomes once again the eternal, with the only difference that it is the eternity of the Laws in which phenomena are resolved, instead of being the eternity of Ideas which would serve as their model. But in one case as in another, we are dealing with theories. Let us stick to the facts. Time is immediately given. This is enough for us and, waiting for its inexistence or perversity to be demonstrated to us, we will simply conclude that there is an effective gushing of unpredictable novelty.

Philosophy will benefit from this by finding some kind of absolute in the moving world of phenomena. But we will also benefit from this by feeling happier and stronger. Happier because the reality that is being invented before our eyes will give each of us, incessantly, certain satisfactions that art procures here and there for those on whom fortune shines. To us it will reveal – beyond the fixedness and monotony which our hypnotized senses initially perceived owing to the constancy of our needs – this renovative and incessant novelty, the moving originality of things. But above all we will be stronger because we, creators of ourselves, will feel that we are participating in the great work of creation that is at the origin and that continues before our very eyes. In pulling ourselves together, our faculty to act will increase. Humiliated until then in a pose of obedience, slaves to who-knows-what natural necessities, we will rise up again, masters associated with an even greater Master. Such is the conclusion of our study. Let us keep seeing a simple game in our speculation about the relationship between the possible and the real. It may be a preparation for living well.

------------------------------------

*** Perhaps again we should ask ourselves whether, in certain cases, the obstacles did not become surmountable thanks to the creative action which surmounted them. This action, unpredictable in itself, would then have created the "surmountability." Before this action, the obstacles were insurmountable and, without this action, they would have remained so.

Bergson in

Bergson in  Essays,

Essays,  French literature and film,

French literature and film,  Translation

Translation