Bergson, "What is a dream?" (part 1)

Tuesday, January 29, 2013 at 15:05

Tuesday, January 29, 2013 at 15:05 The first part of a lecture given at the Institut général psychologique by this French man of letters. You can read the original here.

The subject that the institute invited me to talk to you about is so complex and raises so many problems – some psychological, others physiological and even metaphysical – and would require explanations of such length (and we have so little time), that I request your permission to forgo all prefatory and non-essential remarks and come immediately to the heart of the matter.

So here is a dream: I see marching before me all sorts of objects; none of them exists in reality. I feel that I am coming and going, enduring a series of adventures, when all the while I am asleep in my bed, and quite peacefully at that. I listen to myself speak and I hear how I am answered; nonetheless, I am alone and say nothing. Whence comes this illusion? Why do we perceive people and things as if they were really present?

But first, is there nothing at all? Isn't a certain perceptible material offered to our sight, to our hearing, to our touch, etcetera?

Let us close our eyes and see what happens. Many people will say that nothing happens, but that is because they are not looking attentively. In reality, we notice a great many things. First of all, a black background. Then spots of various colors, sometimes drab, sometimes of a singular clarity. These spots dilate and contract, change forms and nuance, encroach upon one another. The change may be slow and gradual. On occasion this change also takes place with extreme rapidity. Whence comes this phantasmagoria? Physiologists and psychologists have spoken of "luminous dust," "ocular spectra," and "phosphenes"; in any case, they attribute these appearances to slight modifications produced incessantly in the circulation of the retina, or to the pressure which the closed eyelid exerts upon the human eye, mechanically exciting the optic nerve. Yet it matters little what the explanation of the phenomenon may be, or what name we choose to give it. It is found in everyone and it provides, without a doubt, the stuff from which we carve out our dreams.

Alfred Maury and, around the same period, the Marquis d'Hervey de Saint-Denys had both remarked that these colored spots in moving form might be consolidated at the moment of our becoming sleepy, thus sketching the contours of the objects that will compose our dreams. This observation was taken, however, with a grain of salt because it came from psychologists who were half-asleep. G. T. Ladd, an American philosopher and professor at Yale University, has since devised a more rigorous method, if one of difficult application as it requires some training. It involves keeping our eyes closed when we wake and retaining for a few moments the dream that is about to disappear from our field of vision and soon, of course, also from our memory. Here we see the objects of our dreams dissolve into phosphenes and become confounded with the colored spots which the eye really perceived when our eyelids were closed. For example, let's say we were reading a newspaper: this is a dream. We wake up, and from the newspaper, whose lines are fading, we see a white spot with vague black streaks: this is reality. Or we might think of a dream coming to us on the open water. As far as the eye could see, the ocean was nurturing its grey waves crowned in white foam. Upon waking, everything gets lost in a large spot of pale grey sprinkled with brilliant dots. During sleep, therefore, something was offered to our perception, a visual dust, and this dust is used to create dreams.

Is it the only thing used? To speak only about our sense of sight, let us say that beside these visual sensations whose source is internal, there is also an exterior cause. The eyelids may have been closed, yet the eye still distinguishes light and darkness and even recognizes, up to a certain point, the nature of that light. For the sensations provoked by real light lie at the origin of many of our dreams. A candle lit suddenly will evoke in the sleeper, if his sleep is not too deep, an ensemble of visions dominated by the idea of fire. Tissié cites two such examples: "B. dreams that the theater of Alexandria is on fire; the flames illuminate an entire city quarter. All of a sudden he finds himself transported to the center of the basin at Manshieh square; a streak of fire runs along the chains connecting the bounds placed about the basin. Then he finds himself in Paris at the Expo which is on fire ... he witnesses some harrowing scenes, etcetera. He wakes up with a start. His eyes had been taking in the ray of light projected by the dark lantern which the nurse on duty had turned towards his bed when she passed by..."; "M. dreams that he has been engaged by the marine corps, where he once served. He goes to Fort-de-France, to Toulon, to Lorient, to the Crimea, to Constantinople. He sees flashes of lightning; he hears thunder ... finally, he takes part in a battle in which he sees fire leaving the mouths of the cannons ... He wakes up with a start. Like B., he was woken up by the stream of light projected by the dark lantern of the nurse making her rounds." Such are the dreams that can be provoked by vivid and unexpected light.

Very different are those which suggest a continuous, soft light, such as that of the moon. Krauss tells us that one night, as he was waking up, he noticed that he was still extending his arms towards the person who had been, in his dream, a young girl, towards what was nothing more than the moon, amidst whose beams of light he squarely sat. This case is not the only one. It seems that the rays of the moon, caressing the eyes of the sleeper, may have the power of provoking such virginal apparitions. Would this not explain the fable of Endymion, the shepherd forever asleep, whom the goddess Selene (otherwise known as the Moon) loves so profoundly?

The ear also has its interior sensations – buzzing, chiming, whistling – which we make out rather poorly while awake yet which sleep cleanly detaches. What is more, once we are asleep we continue to hear certain noises from outside. The creak of furniture; the crackling fire; the rain beating against the window; the wind playing its chromatic scale in the chimney; as well as other sounds which catch the ear and which dreams convert into conversations, cries, concerts, etcetera. When scissors and tongs are rubbed together before the ears of a sleeping Alfred Maury, we get the following: he immediately dreams that he hears an alarm and that he is witnessing the events of June 1848. I can cite other examples. But one must understand that sounds have as much place in the majority of dreams as forms and colors do. Visual sensations predominate; in fact, often we do nothing more than see although we may believe that we hear at the same time. According to Max Simon, we may even have an entire conversation during a dream and then suddenly realize that no one is speaking and that no one has spoken. It was a direct exchange of thoughts between us and our interlocutor, a silent interview. A strange phenomenon this, and yet one easy to explain. For us to hear sounds in a dream, there generally need to be real sounds that are perceived. With nothing the dream does nothing. And so, when we do not provide our dream with acoustic material, it has trouble creating acoustics.

Moreover, the sense of touch interferes as much as the sense of hearing. Contact and pressure affect consciousness more when one is asleep. As it influences the images that at that moment occupy the field of vision, the sense of touch may be able to modify their form and meaning. Let us suppose that all of a sudden the sleeper feels his shirt touch his body; he will remember that he is dressed lightly. If he were then to believe he was walking down the street, he would think passers-by were gazing at him as he had very little on. Those passers-by would not, however, be shocked, because it is rare that the eccentricities to which we subject ourselves during dreams have any emotional effect on our spectators, regardless of how confused or embarrassed we may be ourselves.

I have just referred to a very well-known dream. And here is another, which many among you must certainly have had. In this dream, we feel we are flying, gliding, and traversing space without touching the earth. In general, when it happens once, it tends to happen again, and at every new experience, we say to ourselves: "I have always dreamed that I was in motion above the ground, but this time I am fully awake. Now I know and I will show others how they can free themselves from the laws of gravity." If you wake up suddenly, this, I believe, is what you will find. You felt that your feet had lost their foothold since you were stretched or spread out. On the other had, thinking you were not asleep, you were not conscious of being in bed. Therefore you said to yourself that you were no longer touching the ground and, what is more, that you were standing up. It was this conviction that developed your dream. Notice that in the cases in which you feel that you are flying, you believe you are launching your body to the right or left side, lifting your arm in a sudden movement as if you were flapping a wing. For this is precisely the side on which you are sleeping. When you awake, you will find that the sensation of making an effort to fly was created by nothing more than the pressure of your arm and body against your bed. This phenomenon, detached from its cause, was nothing more than a vague sensation of fatigue imputable to your effort. Re-attached to the conviction that your body left the earth, it became the precise sensation of making an effort to fly.

It is interesting to see how the sensations of pressure, encompassing even the field of vision and taking advantage of the luminous dust present therein, can be transposed in this field into forms and colors. One day, for example, Max Simon dreamed that he was standing before two piles of gold coins, that these piles were uneven, and that he was trying to even them out. But he did not succeed. Here he experienced a vivid feeling of anxiety. This feeling, increasing from minute to minute, finally woke him up. He then noticed that one of his legs was caught under the folds of his covers, and that his two feet were not at the same level, and were trying in vain to come closer to one another. It is obviously from there that he derived his vague sensation of unevenness, which, having intruded upon the field of vision and finding there perhaps (this is the hypothesis I propose) one or more yellow spots, was expressed visually by the unevenness of two piles of gold coins. Thus there exists, immanent in tactile sensations during sleep, a tendency to visualize ourselves and insert ourselves in such a form into our dreams.

More important still are the sensations of "interior touch" emanating from all points of the organism, in particular from the viscera. Sleep may give them, or rather imbue them with a singular delicateness and acuity. Doubtless they were there during waking hours as well, but since we were distracted from them by other actions, we were living outside of ourselves; sleep has made us return to ourselves. It has happened that people suffering from laryngitis, tonsillitis, etcetera, have found themselves afflicted in the middle of a dream with a disagreeable stinging sensation in their throats. A simple illusion, they tell themselves upon waking. Alas, so quickly does the illusion become reality! We can enumerate serious illnesses and accidents, epilepsy seizures, cardiac afflictions, etcetera, which were discovered this way, prophesied in a dream. We are thus not surprised that philosophers such as Schopenhauer claim that dreams transfer to our consciousness the shocks sustained by our nervous system; that psychologists such as Scherner attribute to each organ the power of provoking specific dreams that represent those organs symbolically; and that doctors such as Artigues have written treatises on the semiological value of dreams, on the manner in which they aid in the diagnosis of illnesses. More recently, Tissié has shown how troubles with digestion, breathing, and circulation can be conveyed in certain types of dreams.

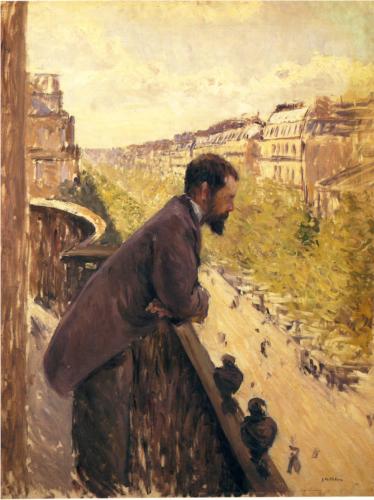

Bergson in

Bergson in  Essays,

Essays,  French literature and film,

French literature and film,  Translation

Translation