A work by this Argentine from one of his later collections, El informe de Brodie. You can read the original here.

For years I stated that I had grown up in Palermo; now I know that this was mere literary braggadocio. The fact is that I grew up on the other side of a long wrought-iron gate of spears, in the house and garden and library of my father and grandparents. Palermo of the knife and guitar would linger (they assure me) around the corners. In 1930, I consecrated a monograph to Carriego, the singer and preacher of our local slums. Chance led me, a bit later, to Emilio Trápani. I was going to Morón; Trápani, who was next to the window, called out to me by name. I didn't recognize him right away: so many years had passed since we shared the same bench in a school on Thames street. Roberto Godel might have recognized him.

For years I stated that I had grown up in Palermo; now I know that this was mere literary braggadocio. The fact is that I grew up on the other side of a long wrought-iron gate of spears, in the house and garden and library of my father and grandparents. Palermo of the knife and guitar would linger (they assure me) around the corners. In 1930, I consecrated a monograph to Carriego, the singer and preacher of our local slums. Chance led me, a bit later, to Emilio Trápani. I was going to Morón; Trápani, who was next to the window, called out to me by name. I didn't recognize him right away: so many years had passed since we shared the same bench in a school on Thames street. Roberto Godel might have recognized him.

We had never been fond of one another. Time had separated us physically but bound us in indifference. I remember now that he had taught me the rudiments of our waggish Buenos Aires slang. We started up one of those trivial conversations so insistent on finding useless facts and resulting in our discovery of the death of a classmate who was now no more than a name. All of a sudden, Trápani said:

"I borrowed your book on Carriego, and you keep going on and on about thugs ... Tell me, Borges, what could you know about thugs?" He looked at me with some kind of holy horror.

"I researched the matter," I answered.

He didn't let me continue and said:

"Researched is the word. But I, you see, I don't need any documents. I know these types of people." After some silence, he added, as if bestowing upon me a secret:

"I am the nephew of Juan Muraña."

Of all the knife throwers of Palermo up to the nineties or so, Juan Muraña was the most talked about. Trápani went on:

"My aunt Florentina was his wife. The story might interest you."

Certain rhetorical emphases and longer phrasings led me to suspect that this was not the first time he was telling this tale.

"My mother, you see, was always disgusted by the fact that her sister joined her life with that of Juan Muraña, who for her was a cruel, heartless being. For my aunt Florentina, however, he was a man of action. Many stories have circulated about the fate of my uncle. One very popular tale was about how one night, after a few drinks, he fell out of the driver's seat of his car trying to pass on the corner of Coronel, and how stones shattered his skull. It is also said that the law pursued him and he fled to Uruguay. My mother, who could never stand her brother-in-law, never explained the matter to me. I was very young and retained no memory of him.

"During the centennial we were living in Russell passage in a long and narrow house. The back door, which was always locked, gave out onto San Salvador. In the attic lived my aunt, already along in years and a bit odd. Bony and gaunt, she was – or at least she appeared to me to be – very tall and frugal in her words. She was scared of being outside and never went out, nor did she want us to enter her room. More than once I caught her stealing and hiding food. Around the neighborhood it was said that the death or disappearance of Muraña had driven her insane; I always remember her in black. She had acquired the habit of talking to herself.

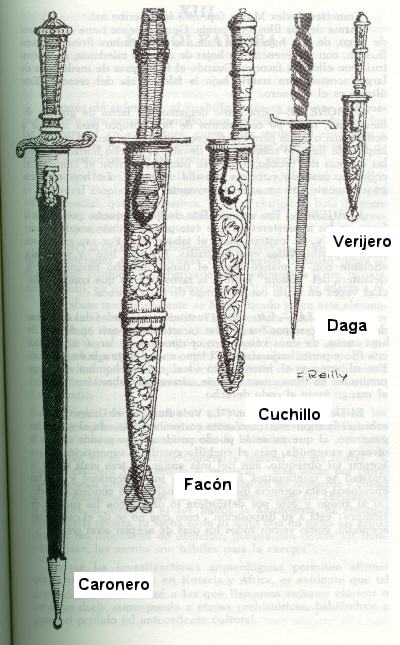

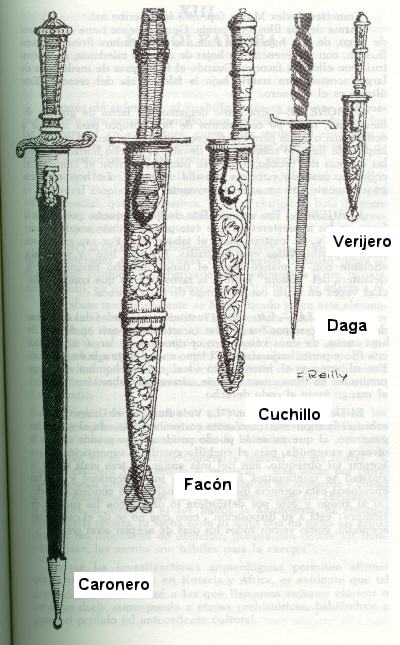

"The house was the property of a certain Mr. Luchessi, owner of a barber's shop in Barracas. My mother, who was a seamstress of some corpulence, was going through a bad time. Without understanding all that was going on, I heard the stealthy words: law enforcement official, eviction for default of payment. My mother was the most affected by all this; my aunt repeated obstinately: Juan would never allow that wop to throw us out. I remembered the case – which we knew by heart – of an insolent bastard from the south of Buenos Aires who had dared to challenge the courage of her husband. Juan, as far as I know, paid his way to the other end of town, sought him out, fixed him with a dagger, and threw him in the Riachuelo. I don't know whether the story is true. But what matters now is that the story is told and believed.

"As for me, you could find me sleeping in the holes of Serrano street begging for alms, or with a basket of peaches. I tried anything to free myself from going to school.

"I don't know how long this foundering went on. Your late father once told us that time could not be measured in days, like money was broken into cents or pesos, because the pesos were equal and every day is different, perhaps even every hour. I didn't quite understand what he meant, but the sentence remained etched in my memory.

"One of those nights I had a dream that became a nightmare. I dreamt of my uncle Juan. I hadn't had a chance to get to know him, but I imagined him Indian-looking, hefty, with a sparse mustache and long hair. We were heading south, between the large quarries and the undergrowth, but these quarries and weeds were also Thames street. In my dream the sun was high. Uncle Juan was in black. He stopped next to a type of scaffolding in a narrow pass. He kept his hand under his jacket at the level of his heart, not like someone who was about to pull out a gun but like someone who was hiding one. In a very sad voice he said to me: I have changed greatly. He took out his hand and what I saw was the claw of a vulture. I woke up screaming in the darkness.

"The next day my mother ordered me to go with her to Luchessi's. I knew that she was going to ask him for an extension; doubtless, I was taken along so that our creditor could see his negligence. She didn't say a word to her sister, who would not have agreed to debase herself in such a manner. I had never been to Barracas; there seemed to be a lot of people, more traffic, and little wasteland. From the corner we saw guards and a group in front of the number we were looking for. A neighbor was walking around telling everyone that shots had rung out towards three in the morning. He had heard the door open and someone come in. No one had closed the door; at dawn they had found Luchessi lying in the hallway half-dressed; he had been stabbed. The man had lived by himself and the police never found the culprit. Nothing had been stolen. One person remembered that towards the end of his life, Luchessi had lost his sight. Another said in an authoritative voice: 'His hour had arrived.' The report and tone impressed me; and as the years passed I came to notice that every time someone died there was always a sententious voice announcing the same discovery.

"The people at the wake invited us for coffee and I had a cup. In the casket there was a wax figure in place of the deceased. I said as much to my mother, and one of the funeral home employees laughed at me and explained that this figure in black clothing was Mr. Luchessi. I was fascinated looking at him, and my mother finally had to take me by the arm and pull me away.

"For months no one talked about anything else. Crimes were rare then; think about how much talking came from the the affair of Melena, Campana, and Silletero. The only person who didn't bat an eyelid was Aunt Florentina. She repeated insistently in her old age:

"'I told them that Juan wouldn't allow that wop to leave us without a roof over our heads.'

"One day it rained and rained. Since I couldn't go to school I started nosing about the house. I went up to the attic. There was my aunt with one hand atop the other; I sensed that even thoughts were not reaching her. The room was dank; in a corner was an iron bed with a rosary on one of its posts; on the other, a wooden case to keep clothes. On one of the whitewashed walls there was the image of the Virgen of Carmen. On top of the small night table was a candle.

"Without raising her eyes, my aunt told me:

"'I knew that you'd come here. Your mother must have sent you. She doesn't understand that it was Juan who saved us.'

"'Juan?' I managed to say. 'Juan died more than ten years ago.'

"'Juan is here,' she said. 'Do you want to see him?'

"She opened the drawer of the night table and pulled out a dagger. She continued talking softly:

"'Here he is. I knew that he would never leave me. There has never been a man like him on this earth. He did not grant that wop any respite.'

"So I was the only one who understood. This poor unwise woman had killed Luchessi. Driven by hate, madness and perhaps, who knows, maybe by love, she had slipped out the door that gazed upon the south, crossed street after street in the middle of the night, arrived at the house, and then with her great bony hands plunged the dagger into his heart. The dagger was Muraña, it was the dead man that she continued to adore. I never knew whether she told my mother. She died just before we were evicted.'"

Until now I have never heard the story of Trápani again. In the tale of this woman who remained alone and who confused her man, her tiger, with this cruel thing that he left her, the weapon of his acts, I begin to see, I think, a symbol of many symbols. Juan Muraña was a man who walked my streets, who knew what men knew, who knew the taste of death and who then became a knife, and now a memory of a knife, and tomorrow oblivion, collective oblivion.

Thursday, March 13, 2014 at 23:12

Thursday, March 13, 2014 at 23:12  He who forsakes to know each grain,

He who forsakes to know each grain,