The Conversation

Tuesday, April 7, 2015 at 14:46

Tuesday, April 7, 2015 at 14:46 For the first few minutes of this film we simply hover. We are drawn down slowly to a street mime, then to a respectable-looking gentleman in a trench coat holding a coffee cup who makes sure that the street mime doesn't accost him. Just as that gentleman comes into focus, however, we start hearing some odd sounds (we are still, it should be noted, a low-flying hawk). Soon we are taken to the possible source of those sounds who is, of course, perfectly soundless, and the cross-hairs of his long, slender sniper rifle. Yet this is not a rifle. Only after enduring a variety of angles do we understand that positioned on the roof of an elegant San Francisco office building is an ultramodern microphone. We are still in the process of witnessing an assassination, albeit one of character not of mortal form, and the device's symbolism as a weapon cannot be understated. What we thought was a rifle is indeed trying to open hearts and minds, to make them bleed for all to see – or at least for some to hear. The targets are a young couple, Ann (Cindy Williams) and Mark (Frederic Forrest), and the mastermind behind this eavesdropping operation is a respectable-looking gentleman in a trench coat by the name of Harry Caul (Gene Hackman).

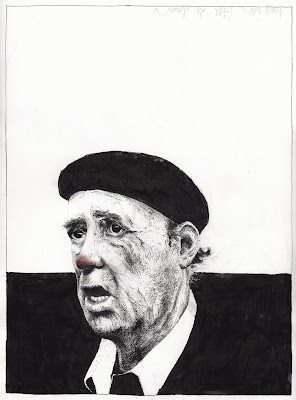

Harry, we soon learn, is a superstar in his field. To avail myself of a contemporary analogy – we are ironically nearing the end of the Nixon era, although Coppola conceived and composed The Conversation years before – Harry is the Jackal of all wiretapping trades. His assignment, which he has accepted with the same sangfroid as so many previous jobs, is to follow Ann and Mark, record every word the lovebirds exchange, remaster the recordings to crystal clarity, then sell them to an unscrupulous corporate aide (a diabolical Harrison Ford). Harry’s collaborators Stan (John Cazale) and Paul (Michael Higgins) wonder and joke about their subjects because “that’s human nature,” but Harry insists on remaining aloof and impassive. “The only thing I want from this is a pile of tape,” he says so peremptorily that Stan quits his employ. After circumstances lead Harry, a guilt-stricken if impious Catholic, to visit his father confessor (a terse scene whose abrupt ending renders it disingenuous), we learn that his vocation has resulted in people getting hurt before. He doesn’t ask questions of those deep-pocketed and curious enough to hire him, so why should he be responsible for the consequences of his snooping? This trope, the notion of responsibility for taking orders, be they staked on self-preservation or, far more unforgivably, large financial gain, is one of cinema’s and, indeed, art’s oldest (you may have seen a movie or two about an emotionless ‘driver’ who takes anyone anywhere for exorbitant fees), and it is one that informs the shape and being of Harry Caul. He may be but a middle-aged nobody, but even middle-aged nobodies can have mistresses (Terri Garr) and hobbies, in Harry’s case, a saxophone always played in accompaniment to, well, a recording.

Harry, we soon learn, is a superstar in his field. To avail myself of a contemporary analogy – we are ironically nearing the end of the Nixon era, although Coppola conceived and composed The Conversation years before – Harry is the Jackal of all wiretapping trades. His assignment, which he has accepted with the same sangfroid as so many previous jobs, is to follow Ann and Mark, record every word the lovebirds exchange, remaster the recordings to crystal clarity, then sell them to an unscrupulous corporate aide (a diabolical Harrison Ford). Harry’s collaborators Stan (John Cazale) and Paul (Michael Higgins) wonder and joke about their subjects because “that’s human nature,” but Harry insists on remaining aloof and impassive. “The only thing I want from this is a pile of tape,” he says so peremptorily that Stan quits his employ. After circumstances lead Harry, a guilt-stricken if impious Catholic, to visit his father confessor (a terse scene whose abrupt ending renders it disingenuous), we learn that his vocation has resulted in people getting hurt before. He doesn’t ask questions of those deep-pocketed and curious enough to hire him, so why should he be responsible for the consequences of his snooping? This trope, the notion of responsibility for taking orders, be they staked on self-preservation or, far more unforgivably, large financial gain, is one of cinema’s and, indeed, art’s oldest (you may have seen a movie or two about an emotionless ‘driver’ who takes anyone anywhere for exorbitant fees), and it is one that informs the shape and being of Harry Caul. He may be but a middle-aged nobody, but even middle-aged nobodies can have mistresses (Terri Garr) and hobbies, in Harry’s case, a saxophone always played in accompaniment to, well, a recording.

With the tapes more or less remastered, Harry makes an appointment with the aide for a cash handoff, especially generous for a day's work and perhaps a week's planning. But something irks him; something isn't right or, at least, what it appears to be. Admittedly, the sleek, serpentine aide, whose name is Martin Stett, and his crooked smile do not inspire much confidence. Harry won't even try an allegedly homemade Christmas cookie until his host has swallowed one and survived. Stett repeatedly prevents Harry from meeting the corporate director bankrolling this scheme – so adamantly, in fact, that, if it weren't for his youth, one would have suspected Stett of being the man he claimed to serve. Somehow, however, we sense that the aide is not the font of evil, but gleefully in the thrall of a greater demon. Reviewing The Conversation I am convinced Harry changes his mind about almost everything on the basis of the timbre of Martin Stett's voice. To his trained, musical ear so adept at making the finest adjustments to achieve perfect audio, something is hideously wrong. In Stett he detects a profound wickedness and becomes terrified (the Catholic elements of Harry's personality, which wax and wane at some of the most inopportune moments, may have played a role). In the film's best scene Harry storms out of Stett's office only to espy someone he never expected to see by the elevators. As he turns away in surprise he glimpses, at the other end of the long hall, a fuzzy, wraith-like figure gently waving a triumphant envelope. Stett seems far away, yet as Harry escapes to the elevator the doors close upon the aide's devious grin like the shutters to some witch's cottage. Thus it is no coincidence that Amy, Harry's unbearably young and unbearably naïve part-time lover, is angelic in every respect and that he subsidizes her apartment with money from people like Stett. Just as uncoincidental is the fact that his birthday comes on the day on which he achieves his masterpiece of surveillance of those two young lovebirds, because a new life has begun. Perhaps, however, unbeknownst to Harry.

Other characters float in Harry's vicinity but their invariable aim is to shed light on our protagonist. Amy's inquiries into Harry's line of work – her discovery that it was his birthday makes her feel like they have come closer – exiles her for the rest of the film. Paul and, in particular, Stan gaze upon Harry in awe, although awe may be the last earthly thing their colleague desires. Harry may be regarded by people in his field as a hero and a genius, but his passion has not made him wealthy; to liken him to an impoverished poet only appreciated by other poets is more than a bit plausible. His foil must then be a rich fraud envious of Harry's untouchable reputation and keen on embarrassing him in front of those who respect him. We get this cardboard cutout in William P. "Bernie" Moran (Allen Garfield). Reviewers have praised Garfield's performance, but his every word and gesture are boilerplate, and we are very relieved when he finally completes his mission (humiliating Harry) and disappears. Yet his annoying presence illuminates aspects of the plot and Harry's scruples, both of which converge in a magnificent warehouse scene where Harry is pursued by Moran's slinky assistant, who turns out to be available on an hourly basis. Harry and this lady, who is neither young nor old, a perfect way to pass a night, will split some sheets, an encounter that evokes a gorgeous nightmare and an explanation for our hero's surname.

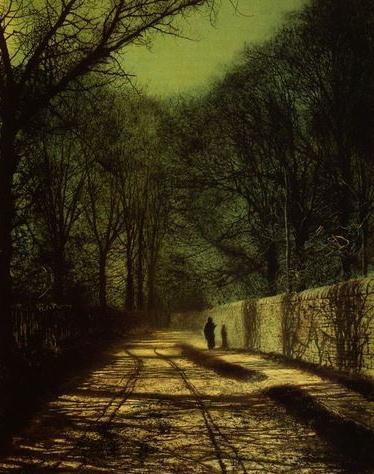

What we have intentionally omitted, of course, is the conversation itself. Without spoiling what has been revealed in countless reviews, the distinct advantage for the audience of The Conversation – and indeed, the film would otherwise be unwatchable – is the pan to Mark and Ann's faces as snippets of dialogue (perhaps the most important has to do with an old hobo) are restored by Harry's wizardry. Are we privy to emotions that Harry can only imagine, or are we seeing what Harry imagines and which did not happen at all? That matter is never resolved, even at the end when some loose ends do appear nicely bowed; as such, we must remain at the full mercy of Harry's interpretation. The innuendo when Harry spends that long and regrettable night with Moran's assistant is heightened by his very conscious choice to fall asleep to the conversation, to let it invade and alter his dreamscape. Harry, you see, is really a Romantic poet in disguise. A Romantic poet who, like a cloud, sits upon the air to dart upon his spellbound prey.