The Master

Friday, July 29, 2016 at 11:14

Friday, July 29, 2016 at 11:14 Man is not an animal. We are not a part of the animal kingdom. We sit far above that crowd, perched as spirits, not beasts. You are not ruled by your emotions. It is not only possible, it is easily achievable that we do away with all negative emotional impulses and bring man back to his inherent state of perfect.

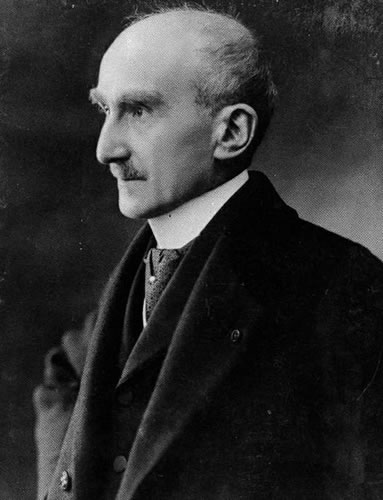

Lancaster Dodd

It is August 1945 and the worst has happened, but not the very worst. Several parts of the world, specifically those parts that have controlled time and history's recording of time, have almost obliterated each other, only to decide that life in whatever form was superior to an endless horizon of death. America, that paladin of democracy and initiative, will take credit for saving the world from fascism; yet America itself played only a limited role. America, you see, is the sole country on this nearly-destroyed earth where anyone can become anything; history is not as important to us as opportunity; and truth, to a certain type of American, will not be vitiated by philosophy or even basic ethics. Truth, like history, like life itself, is simply another opportunity. And a very American notion of truth informs this fine film.

It is August 1945 and the worst has happened, but not the very worst. Several parts of the world, specifically those parts that have controlled time and history's recording of time, have almost obliterated each other, only to decide that life in whatever form was superior to an endless horizon of death. America, that paladin of democracy and initiative, will take credit for saving the world from fascism; yet America itself played only a limited role. America, you see, is the sole country on this nearly-destroyed earth where anyone can become anything; history is not as important to us as opportunity; and truth, to a certain type of American, will not be vitiated by philosophy or even basic ethics. Truth, like history, like life itself, is simply another opportunity. And a very American notion of truth informs this fine film.

Our title character will comprise a chapter in the rather sorry existence of a man called Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix). The war was won and Freddie, young and unsung, was on the most winning side, that of America; yet early scenes indicate that while his physical well-being was more or less maintained, his psyche was irreparably damaged. Freddie may also be familiar to anyone who thinks that alcoholism is a disease and not a choice, but that small point is ultimately irrelevant. What his tattered mind requires is something to distract him long enough for him to drink himself to death. For Freddie Quell no other option remains. His trinity of violence, sex, and drink would interest even the most casual psychologist were it not for the fact that he is not by any measure an interesting person. Subjected to those fake ink blots of fake minds with fake symbols (a blot even cameos in one of the film's posters), he does what any hard-core alcoholic would do when confronted with one of society's innumerable banalities: he contemplates his next drink. Still-frame the shots from this interview, and you see that Phoenix reverts to the same expression again and again, much like a soldier standing in position. That look is one of somewhat timid disbelief, because that is precisely what he is, a timid disbeliever, which could mean that within his soul lurks profound and unexplored spirituality – or perhaps simply profound and unexplored emptiness. "I suffer," he says, attempting a romantic rebaptism of his addiction, "from what people in your line of work call nostalgia," but he doesn't quite complete the story. So when a discharged Freddie Quell moves on to postwar work as a department store photographer, we cannot take our eyes off his skinny back, curved inward like a hollow shell, or a sail to be blown by the wind. And the wind will come in the plump and stately shape of Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman).

Who is Lancaster Dodd? He presents himself like many charlatans, as a man of broad, Renaissance-like talent and titles, so you may never quite answer that question to your satisfaction. Which is precisely Dodd's intent: to persist as an unfinished mystery. The promises that writers of suspense foist upon their readers, premonitions of danger, hints at a nobler past, memories of childhood and of loss, all these blossom amidst Lancaster Dodd's variegated gardens. Perhaps appropriately, then, it is after farm worker Freddie runs through field after lush field (in a spectacular scene that would have been even greater had it been protracted) that he finds the boat Alethia. Alethia, of course, is Greek for truth, yet that fateful evening, Alethia is occupied by one of those fancy, footloose boat parties that are supposed to celebrate life but really end up celebrating the owner of the boat. We see the boat in profile, almost like a blueprint, as Freddie climbs aboard to be awoken later and told by a pretty young girl, a guardian angel, "you're safe, you're at sea," which is usually where one is not safe. Yet the telltale line is Dodd’s own greeting: "You seem so familiar to me.” Freddie chuckles because he does not understand what Dodd is really saying: make me into whomever you need – a father, brother, lover, friend, or priest – it matters little. His claims of having met Freddie in a previous life will find closure, if such closure is truly possible, in the film’s last scenes which are perfectly logical and glorious in their restraint. But until then, it is Dodd’s self-appointed task (one of his books is subtitled, “A gift to Homo Sapiens”) to show Freddie and other malleable sorts that the truth promulgated by The Cause – a suitably vague name for a hopelessly vague organization – is, if not wholly true, then more interesting and revealing than any other truth floating about. He achieves this end through séances the likes of which would not persuade many educated people, as well as recordings such as the one quoted (in full, although it repeats interminably) at the beginning of this review. The psychobabble we witness – and it is most assuredly psychobabble of a very destructive kind – has a narrator, Dodd’s wife Peggy (Amy Adams), who speaks in that slow, deliberate tone reserved for certain foreigners, pedants, and those of waning mental health. If Lancaster Dodd is the face of The Cause, then Peggy Dodd is its treasurer, chief executive officer, and, as aspersed hints indicate, perhaps even the real "master" (she remains pregnant throughout, as if a new world full of ideas were about to hatch). So when she declares that "we record everything through all lifetimes" (at this time a "hypnotized" patient is recalling her parents having sex after she had already been conceived, an embryonic epiphany), we know we have stumbled upon a cult. The only question, of course, is who is really running the show.

Anyone with a fair knowledge of post-war American religious trends will likely identify the most obvious paradigm for The Cause, a topic I will not belabor because, as it were, it doesn't really matter. That is not to say that Dodd's loosely-knit band represents every cult at every time, but rather, should it be forced to percolate through allegoristic filters, every cult in the wake of an unfathomable and horrendous ordeal (according to the director, the film was partly inspired by the theory that religiousness spikes after a war). As such, while The Cause certainly seems like a huckster's paradise, we are not particularly convinced one way or the other. All we can say for sure is that its adherents do not agree on what the Cause really is, in no small part because Dodd does not allow for any degree of what trendy minds like to call 'demystification.' Three examples should suffice: Dodd's initial interview of Freddie, dubbed "informal processing," which may be the film's strongest scene; the very middle, when Freddie, who is obsessed with womanly charms like so many a teenage boy, is beset by a sort of vision; and a later scene in which the two men are jailed overnight in adjoining cells, and Freddie cruelly tells Dodd what he thinks of his labors. The last scene seems like a watershed, but because the participants are drunk and rowdy, it is dismissed shortly thereafter as a misunderstanding; the initial interview likewise suggests that we are going to get to know Freddie Quell very intimately, but Freddie Quell is a talented fibber; which leaves that odd mid-film scene. Especially odd, because if we are to understand the vision as emanating solely from Freddie's mind, then he has already given up on the cult's promise to feed, clothe, and house him, not to mention provide him with a surrogate family. Considering how little he has in life, this abandonment might seem very rash indeed – unless Freddie Quell is not quite the simpleton he appears to be.

Although released to much critical acclaim, The Master has endured from its scattered disbelievers one uniform complaint: that of dullness and uneventfulness, an assessment both rash and predictable. Anderson’s film certainly has few events, if by events we mean explosions of human bodies inwardly or outwardly, or of historical happenings, of which the film makes little fanfare because Freddie Quell is not Freddie Gump. He has no symbolic agenda as an everyman or holy fool; he is simply a cipher who may merit redemption, but whose main aim is to extend the mortal pleasure of drunkenness. As such, the film is intentionally opaque because the movement it depicts is intentionally opaque, and The Master is mesmerizing, hollow, and well-acted and crafted just like the Dodds appear to have scripts for every occasion. The film's genius resides, however, in Freddie Quell's unconventional transformation. Instead of evolving, as would befit almost every other tale, from a sad sack into a fervent acolyte who will be disappointed with the cult's shortcomings, try to escape, and be confronted with his priests' mercilessness, Freddie undergoes a completely different change: he reverts to the person he was before the war. Since I have purposefully not described the pre-war Freddie, nothing is spoiled by this revelation. Phoenix manages by some technique hitherto unknown to man to cloak his natural wit and vibrancy in a dull glaze without either overacting or underacting, rendering this shift not only believable, but the best possible resolution. And if Freddie's final interlocutor is any indication, then there will always be opportunities for the Lancaster Dodds of the world. For even if we cannot recall any predecessors, we can surely imagine them.