The Captain of the Polestar

Saturday, December 5, 2009 at 17:41

Saturday, December 5, 2009 at 17:41 The man becomes a greater mystery every day, though I fear that the solution which he has himself suggested is the correct one, and that his reason is affected. I do not think that a guilty conscience has anything to do with his behavior. The idea is a popular one among the officers and, I believe, the crew; but I have seen nothing to support it. He has not the air of a guilty man, but of one who has had terrible usage at the hands of fortune, and who should be regarded as a martyr rather than a criminal.

Perhaps I am naturally suspicious of those described as well-read because it implies that reading an indefinite amount of books can convert an average human being into an extraordinary one. Yet man cannot learn on reading alone. Life in its myriad tragedies and triumphs must imbue a learned person with perspective on his shelves that cannot be gained if he never abandons their side. The dialogue of two Victorian lovers will only sound stilted if one has heard two contemporaries mutter sweet nothings; the desperation of frustrated dreams and private pain will only resound if the reader can reflect upon his own losses; and the postmodern, relativist nonsense that masquerades as deep thinking will only be exposed to the mind who knows the history of letters and also knows garbage when he smells it. That is not to say, of course, that we should succumb to the adolescent habit of masking the cast of fiction with faces from our own reality. One finds, I think, certain faces and manners – be they of people we know personally, those of certain celebrity, or odd amalgams not immediately traceable – particularly enchanting, and it is they who become our regulars, our fetished players. We may even discover that we are haunted by images beyond our ken summoned only as fiction dictates – which brings us to this tale of unease.

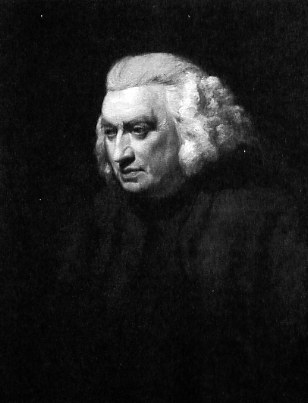

Our narrator is John McAlister Ray, Jr. (which may remind readers of the usher to this novel), a skeptical man of science who apparently learned nothing from his father, also a doctor, who appears towards the story's end in very unusual circumstances. Ray is commissioned for reasons still unclear to us to an Arctic whaler commanded by Captain Craigie. There are some gestures in the direction of this magnificent work – Craigie's bizarre, almost pathological obsession with reaching a certain point in the trajectory, his seeming insouciance for the welfare of his crew, and his sudden outbursts of violent rage – but they are quickly subsumed under the carapace of another tale: a ghostly white figure floating over the seas of ice has been sighted by several members of the fifty-man company. Craigie is "remarkably well read" and has "the power of expressing his opinion forcibly without appearing to be dogmatic"; he also has a particular hue to him that may or may not mark his character:

A man's outer case generally gives some indication of the soul within. The captain is tall and well-formed, with a dark, handsome face and a curious way of twitching his limb, which may arise from nervousness or be simply an outcome of his excessive energy. His jaw and whole cast of countenance is manly and resolute, but the eyes are the distinctive feature of his face. They are of the very darkest hazel, bright and eager, with a singular mixture of recklessness in their expression, and of something else which I have sometimes thought was more allied with horror than with any other emotion.

How eyes can be "of the very darkest hazel" and yet "bright" at the same time comprises one of the conventions of art that may confuse those who only read to pass the time or those who never read anything at all. Somewhere, from among the thousands of faces we have gazed upon and their twinned portals, we can imagine exactly what the effect of these eyes might be. What we cannot imagine is what they conspire to behold in both sleep and waking hours.

The secret of the Polestar's skipper may not really be a secret at all. The atmosphere created is so conducive to terror, however, that we are almost obliged to take the whole series of events – if that is the right word – at face value, something that Ray is very hesitant to do. Our story evolves in journal entries that monitor the crew's dwindling supplies and mounting anxiety. Ray even misses the birthday of his fiancée, his beloved Flora to whom no one could possibly compare, while the sailors lament Craigie's extended circuit because herring season, the most profitable time of the year, begins in short order. It is here that Ray comes across an item of unavoidable interest in the captain's quarters:

It is a bare little room, containing a washing-stand and a few books, but little else in the way of luxury except some pictures on the walls. The majority of these are small cheap oleographs, but there was one watercolor sketch of the head of a young lady which arrested my attention. It was evidently a portrait, and not one of those fancy types of female beauty which sailors particularly affect. No artist could have evolved from his own mind such a curious mixture of character and weakness. The languid, dreamy eyes, with their drooping lashes, and the broad, low brow, unruffled by thought or care, were in strong contrast with the clean-cut, prominent jaw and the resolute set of the lower lip. Underneath it in one of the corners was written M.B., aet. 19. That anyone in the short space of nineteen years of existence could develop such strength of will as was stamped on her face seemed to me at the time to be well-nigh incredible. She must have been an extraordinary woman.

Could Ray be thinking specifically of his own favorite? Perhaps the attitude conveyed so unambiguously by the artist may explain what we learn as our story resolves itself into a certain coherence. That is, if you consider what happens in one of the planet's most silent regions to be resolved.